Explaining Chesterton on truth and logic

Along with a Reidian defense of online trolling

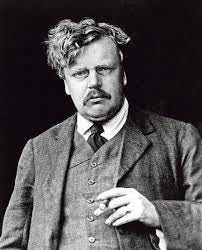

G.K. Chesterton once said,

you can only find truth with logic if you have already found truth without it.1

He is correct if we understand him rightly.

Logic is the science of inference. But inference from what to what? From premise to conclusion. So we can know a conclusion if we know the premises which logically imply it. But how do we know the premises? Well, we can infer them as conclusions from other premises or we can know them without logically inferring them.

Chesterton is saying that we have to know some truths without logically inferring them. The reason is that, if knowing a truth required logically inferring it, we could not know anything at all. We’d have an infinite regress on our hands: we know a conclusion because we know premises A and B which logically imply it; but we only know premises A and B are true if we logically infer them from other premises C and D; but we only know C and D are true if we logically infer them from E and F; but we only… and so on, ad infinitum.

The moral of the story: logic is useless if you don’t already have some truths at the outset.2 The buck has to stop somewhere, and it stops at rock bottom with foundational truths that we cannot deny if we want to use reasoning at all. Philosophers call these first principles.

With Chesterton’s meaning laid bare, we are able to appreciate several famous (and famously witty) remarks on first principles by the Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid, who was a contemporary of David Hume.3

One first principle would be that our faculties of reasoning or perception, though not infallible, are generally reliable and ordered to truth. Reid takes the skeptic to task for questioning some faculties (such as perception), since the same questioning would cut against other faculties (such as reasoning, which the skeptic must rely on):

The sceptic asks me, Why do you believe the existence of the external object which you perceive? This belief, sir, is none of my manufacture; it came from the mint of Nature; it bears her image and superscription; and, if it is not right, the fault is not mine: I even took it upon trust, and without suspicion. Reason, says the sceptic, is the only judge of truth, and you ought to throw off every opinion and every belief that is not grounded on reason. Why, sir, should I believe the faculty of reason more than that of perception?—they came both out of the same shop, and were made by the same artist; and if he puts one piece of false ware into my hands, what should hinder him from putting another?4

A defense of online trolling?

Reasoning, said Jonathan Swift, will never make a man correct an ill opinion, which by reasoning he never acquired.

If you can’t reason with someone, what else can you do? Might we appeal to Reid for a defense of online trolling as a weapon against anyone who denies first principles? To this question, I commend the following passages to the reader, and leave to him the task of determining the answer:

[We] may observe, that opinions which contradict first principles [i.e., those on which reasoning itself presupposes] are distinguished from other errors by this—that they are not only false, but absurd; and, to discountenance absurdity, nature has given us a particular emotion—to wit, that of ridicule—which seems intended for this very purpose of putting out of countenance what is absurd, either in opinion or practice. This weapon, when properly applied, cuts with as keen an edge as argument. Nature has furnished us with the first [i.e., ridicule] to expose absurdity, as with the last [i.e., argument or reasoning] to refute error. Both are well fitted for their several offices, and are equally friendly to truth, when properly used.5 [emphasis mine]

Since reasoning presupposes first principles, you cannot by reasoning reject them. And the man who rejects them, having rejected reason too, is unlikely to be swayed by any argument we supply. Hence, as Reid notes, we are designed to use ridicule as the only remaining tool by which to expose and dismiss the absurd.

To solidify the point, I leave the final word to Reid:

A man that disbelieves his own existence, is surely as unfit to be reasoned with, as a man that believes he is made of glass. There may be disorders in the human frame that may produce such extravagancies; but they will never be cured by reasoning.6

It would seem that ridicule, used properly, is a last defense against the absurd.

The full quote for nerds who want to see it:

Logic and truth, as a matter of fact, have very little to do with each other. Logic is concerned merely with the fidelity and accuracy with which a certain process is performed, a process which can be performed with any materials, with any assumption. You can be as logical about griffins and basilisks as about sheep and pigs. On the assumption that a man has two ears, it is good logic that three men have six ears, but on the assumption that a man has four ears, it is equally good logic that three men have twelve. And the power of seeing how many ears the average man, as a fact, possesses, the power of counting a gentleman's ears accurately and without mathematical confusion, is not a logical thing but a primary and direct experience, like a physical sense, like a religious vision. The power of counting ears may be limited by a blow on the head; it may be disturbed and even augmented by two bottles of champagne; but it cannot be affected by argument. Logic has again and again been expended, and expended most brilliantly and effectively, on things that do not exist at all. There is far more logic, more sustained consistency of the mind, in the science of heraldry than in the science of biology. There is more logic in Alice in Wonderland than in the Statute Book or the Blue Books. The relations of logic to truth depend, then, not upon its perfection as logic, but upon certain pre-logical faculties and certain pre-logical discoveries, upon the possession of those faculties, upon the power of making those discoveries. If a man starts with certain assumptions, he may be a good logician and a good citizen, a wise man, a successful figure. If he starts with certain other assumptions, he may be an equally good logician and a bankrupt, a criminal, a raving lunatic. Logic, then, is not necessarily an instrument for finding truth; on the contrary, truth is necessarily an instrument for using logic—for using it, that is, for the discovery of further truth and for the profit of humanity. Briefly, you can only find truth with logic if you have already found truth without it. [emphasis mine]

(Daily News, Feb 25, 1905.)

The savvy internet surfer may charge me with plagiarism when he discovers that the foregoing remarks match the answer given to this Quora question. I will deny the charge, since the Quora author is none other than Yours Truly.

Reid holds a special place in my heart. Had I not dropped out of my PhD, I would have written on dissertation on something related to him.

Chapter VI (“Of seeing”) section 20, An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense.

Essay VI, chapter 4 (“Of first principles in general”), Essays on the Intellectual Powers of the Human Mind.

Chapter I (“Introduction”) section 3, Inquiry.

Thanks for the post!

It reminds me of when I taught introduction to psychology. I would begin the class by showing them the scene from "Monty Python and the Holy Grail" about witch burning (https://youtu.be/SfKh80BHSnk?si=b6FRL2EVcNoiiN6J). I would ask the students what was wrong with the argument used to determine the woman is a witch.

They would begin with rather sober arguments based in logic but would very quickly get frustrated when I pointed out the flaws in their critiques. Eventually, they would give up and ask, "Ok, what's the problem with the argument?"

"There are," I would tell them, "no such things as witches." And here is Chesterton's point (and my about psychology as a science) our arguments are only as good as our presuppositions. If we begin with false presuppositions, then even the best logic (or empirical science) will lead us to false conclusions.

Thanks again for the post!

In Christ,

Fr Gregory